True Names and the Semantic Web

asdf Note: Without the background of the previous notes some of these considerations might be difficult to follow.

If the main topic of the first three posts has been a classical literary analysis, it’s now time for a more unusual look. Le Guin’s true names and her Old Speech are a fascinating concept not only for her take on an utopia of authenticity that we’ve discussed so far. It is also stimulating for the discussion of something else entirely, seemingly far more technical, the Semantic Web.

The Semantic Web is a “common framework that allows data to be shared and reused across application, enterprise, and community boundaries”[^f1] by creating a web of data. It has certainly many strictly technical aspects such as data formats and exchange protocols, but above all it is a linguistic and semiotic challenge. The Semantic Web is crucially about finding names for things in the real world — things that may be very concrete or quite abstract. To be sure, these names are not necessarily Le Guin’s true names, but they must be unique names nevertheless, and names that do have certain magical properties. Names that help bringing together phrases using this name and hence being about the concept it designates from the most disparate data sources across the planet into a uniform picture. In much of a sense, their magic is that of Ged’s power to summon and control anything whose true name he has learnt.

[^f1] http://www.w3.org/2001/sw/

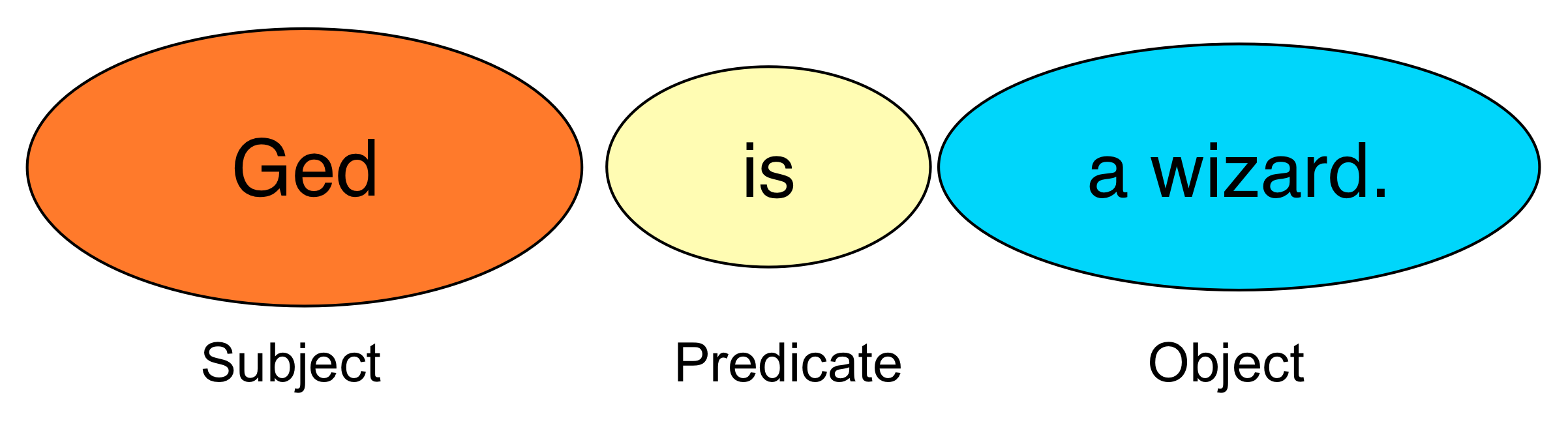

The underlying language of the Semantic Web, the Resource Description Framework (RDF) has fundamentally the syntax of a very simple natural language, using a sentence structure of subject, predicate and object[^fn2]. For a change, it’s not Socrates, but Ged who has to serve as an example:

[^fn2] All the other syntactic constructs of RDF are building on the same triple structure and can for the purposes of this blog post be safely ignored.

That I use Ged’s true name in this example and not his use name Sparrowhawk is strikingly in the spirit of the Semantic Web. Except, of course, that the Semantic Web doesn’t use “normal” names, but a specific machine-readable way of writing of them in the form of Uniform Resource Identifiers or URIs. In fact, and probably to his horror Ged actually does have this true name publicly exposed in the language of the Semantic Web: http://live.dbpedia.org/page/Ged_(Earthsea)

Now, some adherents of the Semantic Web might actually mistake this URI for a “true” name in the sense Le Guin imagined it for Earthsea. However, even the most naive adherents would have to admit that this name is based purely on convention, not on a “correspondence in fact” like the one Le Guin postulates for true names. It is in Peirce’s terminology a symbol and in Saussure’s words a signifiant, and like all signifiants it is at best unique within one language, and not necessarily even that. In fact, Ged has at least two more URIs designating him in the semantic web space, http://www.freebase.com/view/m/0c3nz8 and http://yago-knowledge.org/resource/Ged_(Earthsea).

In this case all three signifiants designate exactly one signifié, namely the fictional wizard in Earthsea. This is largely in line with Le Guin’s utopia which lives in a world of proper names, though even there the situation is unclearer for plants, animals and inanimate things where their use in spells seems to suggest that these are named as “natural classes” such as hawks, otaks or boats. But also in this case true names are intimately linked to the objects they name and the underlying generalizations remain grounded in fact. For these in fact “no thing can have two true names”[^fn3].

[^fn3] As George Lakoff in Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. What Categories Reveal about the Mind, 1990, demonstrates, this type of concrete conceptualizations are much less influenced by the social and cultural superstructure than one might imagine.

The real issue starts when we move to naming man-made social constructs, those that Giambattista Vico in Scienza Nuova famously claimed to be the only ones truly understandable by man[^fn4]. In fact, for naming the contrary is true. Even when we restrict ourselves to names of individual man-made entities rather than classes of concepts, things are getting complicated. What is the true name of, e.g., a city or a country, and does it even have one? Has the London of today, having grown geographically beyond recognition, the same identity as the town Shakespeare worked in? Is the US of 1788 with the thirteen original colonies the same as today’s with fifty states? Is the Kingdom of Italy before 1870, i.e. before the capture of Rome, or for that matter also after that, the same entity as today’s Republic of Italy? In our man-made world, we’re not in the enviable situation that everything has a clear and unambiguous identity, and precisely because it is situated inside history and continuous conflict, everything is in constant flux. We live neither in Le Guin’s utopia of authenticity nor do we share in Vico’s truth based on an objective scienza degli uomini. Instead, we have to name permanent change. In the next post I’ll nevertheless try to explore further what identity can mean inside History.

[^fn4] “che non tramonta, di questa veritá, la quale non si puô a patto alcuno chiamar in dubbio: che questo mondo civile egli certamente è stato fatto dagli uomini, onde se ne possono, perché se ne debbono, ritruovare i principi dentro le modificazioni della nostra medesima mente umana. Lo che, a chiunque vi rifletta, dee recar maraviglia come tutti i filosofi seriosamente si studiarono di conseguire la scienza di questo mondo naturale […] e traccurarono di meditare su questo mondo delle nazione, o sia mondo civile, del quale, perché l’avevano fatto gli uomini, ne potevano conseguire la scienza degli uomini”, G. Vico, F. Nicolini (ed.): La Scienza Nuova. Giusta l’Edizione del 1744, p. 117f.